Visiting artist professor

2016 - 2017 / 2017 - 2018 / 2018 - 2019 / 2019 - 2020

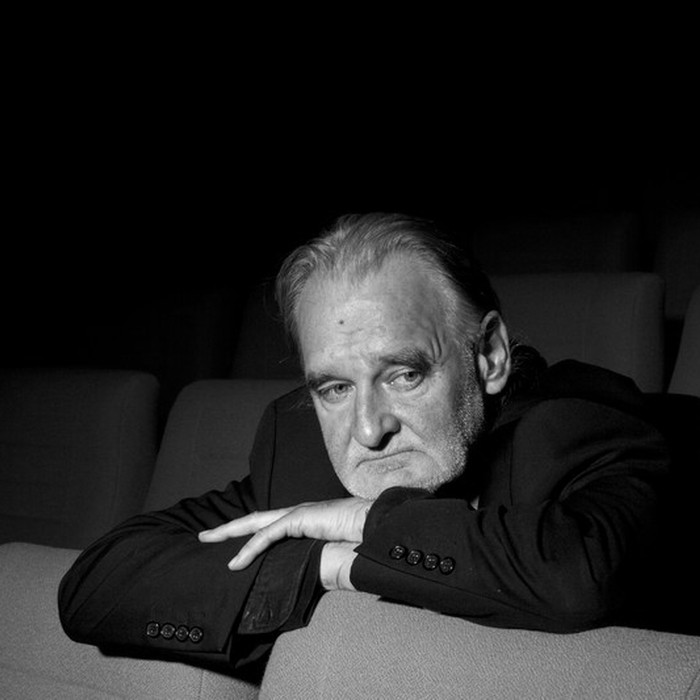

Béla Tarr

Born in 1955 in Pecs (Hungary)

Died in 2026 at Budapest (Hungary)

The nine films made by the Hungarian Béla Tarr between 1979 and 2011 amount to one of the most powerful and influential bodies of work in contemporary cinema. Jacques Rancière, who has written a book about the filmmaker, sees him as a major artist of the "after-time" (1) that followed the failure of the communist promise, whose long sequence shots manage to smash the cycles of repetition by the quality of their attention to the still intact belief in a better life. There will be no tenth film. Tarr decided to retire after making The Turin Horse (2011). Emmanuel Burdeau interviewed him for artpress when he was visiting artist at Le Fresnoy in autumn 2016.

Excerpts follow.

I knew if I could make the movie I wanted, it would be the last one. After Turin Horse, I think I had said everything about life, about people, about everything. Filmmaking is a kind of drug, I was addicted, it's hard to stop when you are a junky. But I don't want to repeat myself. That has never interested me. I developed my style, or whatever you call it, step by step. Each film raises new questions. Slowly I went up, up, up or down, down, doesn't matter how you say it. I could make other films, I'm always getting offers: "Sign here and do what you want." No, I'm not interested. I still have the desire to do things, but surely not a film.

How did you learn to make films?

From life. Everything always comes from life: situations, how people treat a concrete situation. I just watched it and decided to shoot it. Where do you put the camera? This is a moral decision. This is all I can give to the students.

In 2013 I opened the Film Factory in Sarajevo. I always try to make students aware of this question. We have to respect and serve human dignity. You cannot really teach this, but maybe you can help someone to develop it. I made my first feature, The Family Nest, before film school. I was twenty-two, I did not want to knock on the door, to be polite. I wanted to kick the door and say fuck off. I loved cinema and what I saw at that time was fake, far from life or people. This was in 1977, already the end of the New Waves of the Sixties. Film language became industrial, everything was predictable. [...] A proper film school should protect the students from the capitalist system, give them the chance to shoot what they really want, to give them freedom. [...] The Film Factory is unlike any other school, though our concept is a little bit like the Bauhaus, mixing experienced guys and beginners. Teaching art is impossible, in my opinion. All you can do is give young people a chance to discover life, the world, and react to it. I can be proud, because of what we have done in three and a half years. But the programme is expensive and we don't get support from anywhere, so the school is closing. It may open again somewhere else. For me it's a bit like a travelling circus.

Students can be poisoned by art. They believe they're artists. I tell them no. To be an artist is a kind of award, a prize, a decoration. You are a worker. If your work touches people, then you can say you're an artist. It's not your decision. They have to go back to life, that's the main issue---not only everyday life, but life at every level: nature, conflicts, social tensions, everything.